New Blogs from Sustaining Photography ?

Lizzie King and Gwen Riley Jones share recipies and reflections from Sustaining Photography in four new blog posts.

Lizzie King and Gwen Riley Jones share recipies and reflections from Sustaining Photography in four new blog posts.

The University of Salford Art Collection and Castlefield Gallery present Salford Scholars at The Manchester Contemporary 2023.

Lizzie King and Gwen Riley Jones present Sustaining Photography, an exhibition exploring plant-based alternatives to traditional photography PLUS an exciting engagement programme.

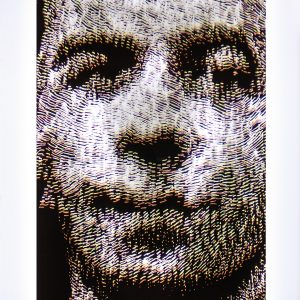

"Visibilities manifests as a focused, thoughtful display that brings works together to address diversity, both in regional communities, and globally." Mike Pinnington, The Double Negative

Art Collection Team Assistant Rowan, who curated Visibilities, our current exhibition at the New Adelphi, dives deeper into one of the artworks on display for August's Artwork of the Month.

Join Visibilities curator Rowan Pritchard, with Stephanie Fletcher (Art Collection, Assistant Curator) for a lunchtime tour of Visibilities: Shaping a story of now.

The University of Salford Art Collection & Castlefield Gallery announce the five graduate artists awarded a place on annual Graduate Sholarship Programme.

The University of Salford Art Collection is delighted to announce Emily Speed as the second artist-in-residence with Energy House 2.0, in partnership with Castlefield Gallery.

The Team has been awarded two Green Impact National Awards: Innovation for Engagement and Sustainability Hero, for their continuing commitment to sustainability action and engagement.

Launching Hybrid Futures, a multi-part collaboration focusing on climate, sustainability, collaborative learning and co-production.