I was lucky enough to be invited to write and reflect upon the work of the many-faceted South African artist Albert Adams, including a brief delve into his archives which are held at the University of Salford Art Collection. An opportunity also arose for me to produce an essay on Adams for Art UK, which you can read here. In that piece I took an introductory approach to the artist, reflecting my own learning, and in this piece I wanted to take a more eclectic approach, allowing me to range between themes and pieces that grabbed my imagination. From learning to yearning, you might say. That’s not just down to my own taste, but also because Adams’ output is not at all linear in its development, though there are themes that he returns to again and again – violence, self, power, nature – in fractured and inconclusive ways. I’m interested in the materials, anecdotes and images that merge/emerge in his work, from forgotten works to the frequent appearance of the artist’s own face, to queer contexts, to the mischievous frightening ape that sits atop it all.

– Greg Thorpe, Oct 2022

‘Hung where they had been painted’

I want to start with an image that might seem innocuous at first. In his short book on Albert Adams, ‘Notes about a Friend’, the renowned Salford artist Harold Riley recalls a visit he once made to Adams’ family in South Africa. He took tea with Albert’s mother and sister in their home, “a simple house in a community, similar to a local council estate in England.”:

as we sat in the room, I saw something from the window. Behind the house was a yard bounded by two sturdy brick outbuildings. I saw something on the walls and went out to discover two paintings of great power and energy. They were hung where they had been painted, and although covered by a kind of veranda, they were open to the elements. I mentioned this to Albert’s sister who nodded but was clearly at a loss as to what to do.

Riley’s discovery is poignant and without conclusion. He later mentions the paintings to Albert’s partner, Ted, who already seems aware of their existence. Were they paintings from Albert’s young life, or had he painted them on a later visit to his family? It’s conceivable that Adams drew and painted everywhere he went, as he seems to have been extremely dedicated to his work. Did he travel to his mother’s house with blank canvases, then back to London without them? Or did he buy materials on arrival in South Africa without worrying what would happen to the abandoned paintings once they were left behind, when light and moisture, wind and weather took its gradual toll? This too is conceivable – Riley himself recalls how Adams only kept “five or six pieces of any significance” from their time together at the Slade School in London. Perhaps the works were meant as a gift for his mother, for the garden, to surprise and intrigue visitors to the house, exactly as they have done.

What was “the great power and energy” Harold Riley saw in the paintings? Where are they now? Why does this odd mention of the two unclaimed veranda paintings linger? Firstly it suggests a sense of abundance to Adams’ output – that there will always be more paintings to come. There is also a forlorn feeling about Riley’s discovery – a sense that perhaps nobody quite knew what to do with Albert’s work, then or now. Are the pieces really ‘unclaimed’ though? What would ‘claiming’ them mean? There is an acquisitiveness to this response, a sense of wanting – to keep, restore, recoup, save. Who says the work of a Black/Indian artist is better off in a gallery or archive setting that is part of a white-dominated art structure than it is hanging where it has been painted in the warm breeze of a Cape Town backyard owned by two women who loved him? Perhaps there is a colonialist mindset at play in wanting to ‘claim’ the work – and a resistance to it in the casualness of what is ‘left behind’.

Notes on the many self-portraits of Albert Adams

Look closely at your lines again –

Your life comes back through them

– ‘Self Portrait 1956’, Jackie Kay

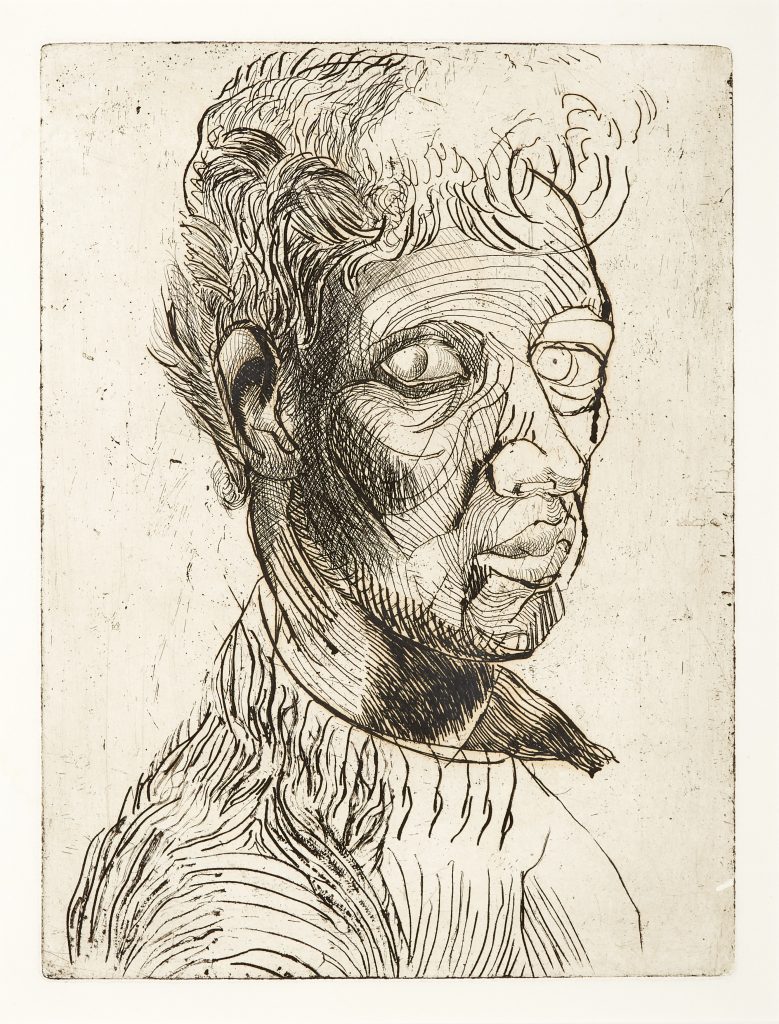

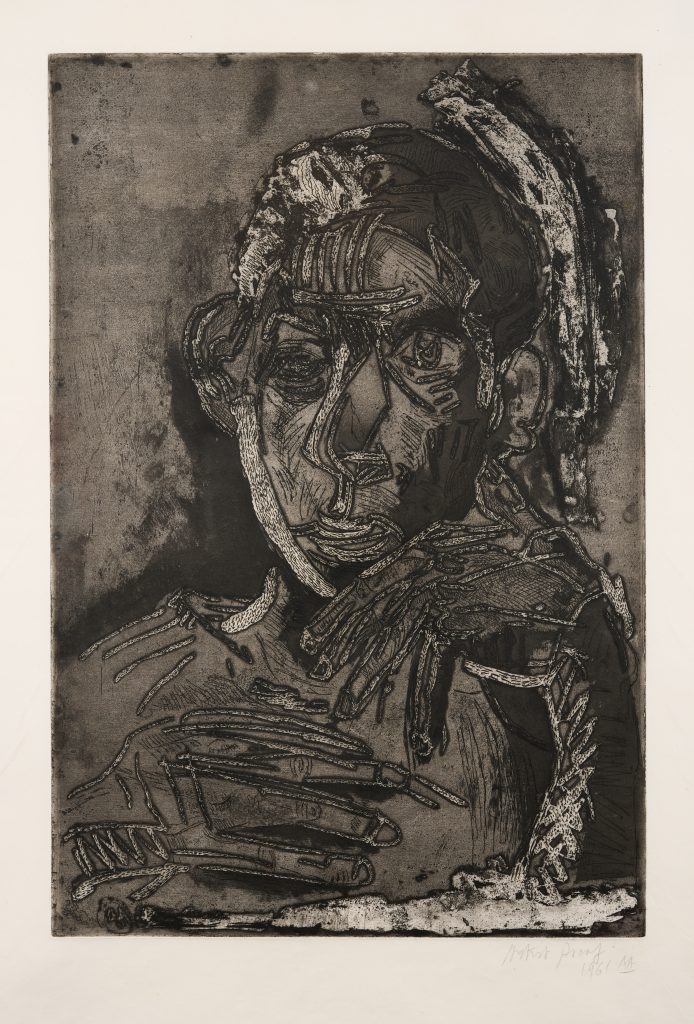

1956, etching on paper: Side-on view, high collar and quiff, almost coquettish this look, giving soft butch like a young Black James Dean (it’s the year of Giant). 26 or 27. High youthful cheekbones elegantly rendered with cartographic contour lines. Are these ‘the lines of South Africa etched in your face’ that Jackie Kay describes? Pristine mouth. Shy cruising eye.

1956, drypoint etching: You first scratch the image onto metal (copper or zinc) then smooth over generously and neatly with ink, then the paper is pressed to plate giving life to the image in its new iteration. Draw the lines nearer together for density or darkness – but the dour expression is all the artist’s own. Glum. Perplexed? I think etched at night in a small hot room.

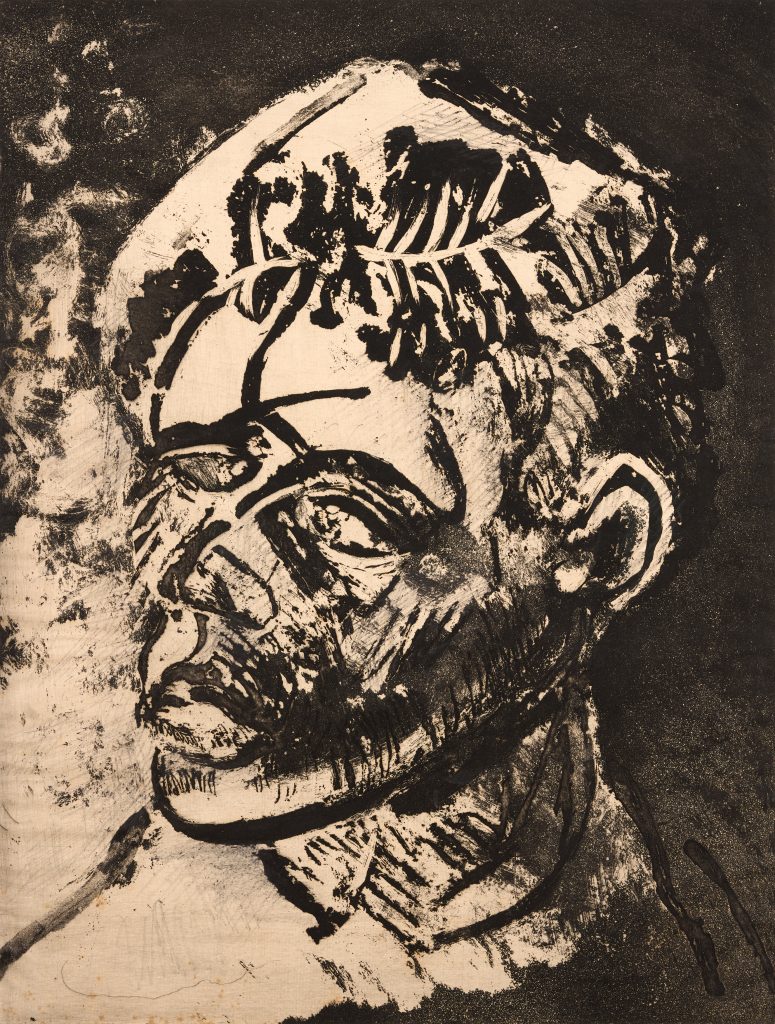

1958, woodcut: New etching techniques bring out Picassan facial features and a feeling of accomplished looking. Minotaur. Simian. Up-lit but emitting darkness. What has happened in these two years? Deft, dynamic – derivative? – but also daring. What does it mean for an African artist to take back what Picasso took from African art? How can we sense so well that black and white represent the same kind of skin in this image?

1958, oil on canvas: Experimenting with colours in oil. Handsome in his vest, such an image ahead of its time – this could be Soho trade lit behind the window of a bar in the 90s. Fast strokes and furious curious lines. Something anticipates Basquiat in the carnival of colours going on behind the scenes. A pretty boy offering us his best side under Tibetan flags. A paperback anthology of rad young poets of colour.

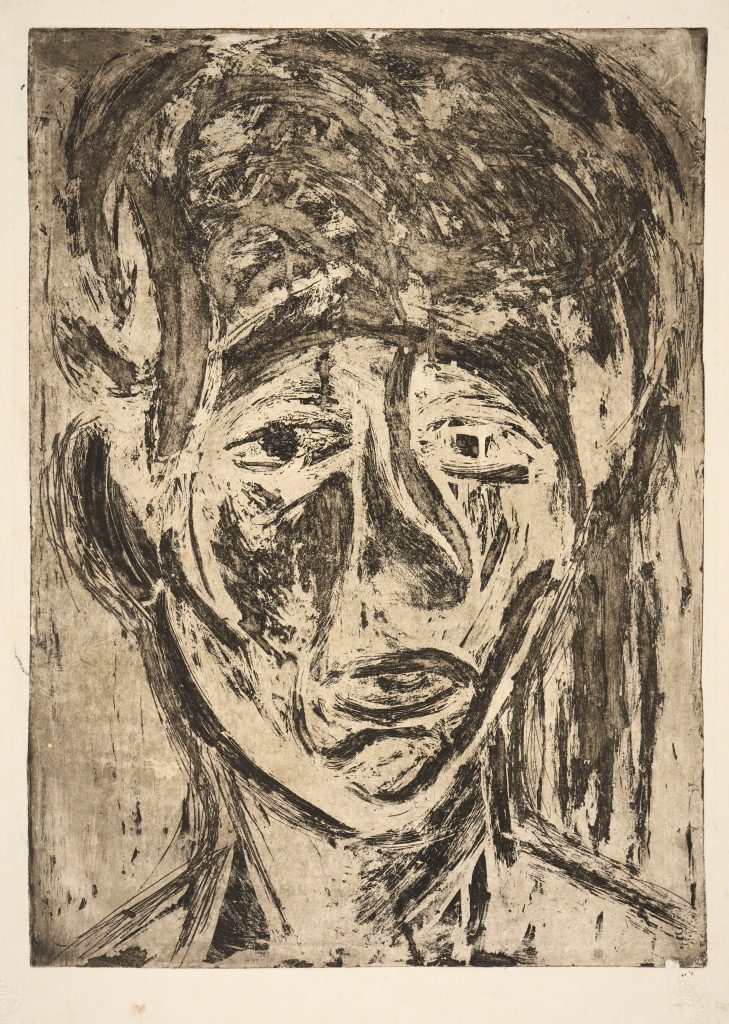

1960, sugar lift aquatint: Ever the technician, hungry for new materials. Back to black, zinc and ink, real sugar, gouache and gum. Sounds thick and sticky but the results give something Grecian and elegant. Is Adams trying to learn each new stage of his craft in solitude – hence his own face over and again? – or does each portrait demand a different form in which to say something new about himself? Introspection. Be still. Focus. Albert falls into shadow here and the eyes seem to go … nowhere. But London is outside your window, Albert!

1960, print: A dead-on pose for once, with lustrous hair and direct eye contact. Like a bathroom mirror beginning to fog up and drip. There are no two portraits alike, because no two days alike? What was kept and what was thrown away, and why, in these years? Adams becoming the Expressionistic printmaker capturing his own cool stare and solemnity, but there is chaos here too – in the energy of the hair that might also be the brain, the mind.

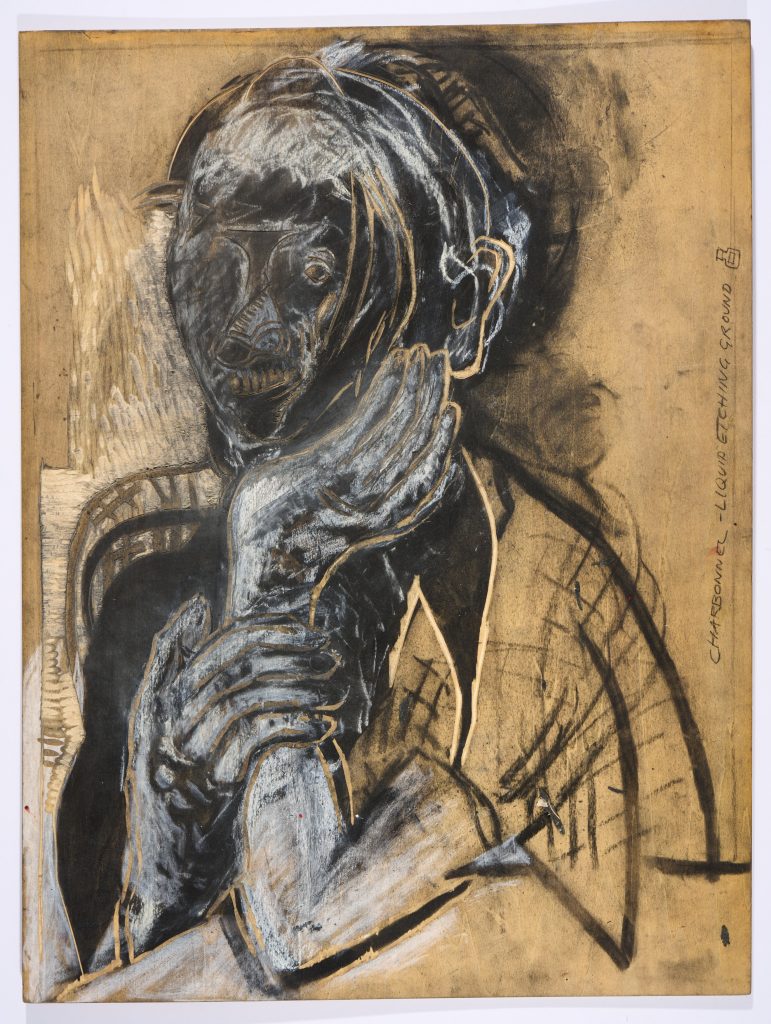

1961, etching and aquatint: 1961, the year of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, South Africa exiting the Commonwealth, Yuri Gagarin entering outer space. Albert’s face here seems to consist of pressings of bark and clay, such texture and tactility. It wants to be touched. Those pale slashes seem like a kind of solarization of matter somehow. This work would be made on an iPad today. It’s the hands that I think are the masterpiece of design and suggestion and structure. Look at that network of metacarpal and knuckle and nail. The busy hands of the artist. Is that a knife or a brush too? Hands as crucial as the face.

Queer considerations in the work of Albert Adams

but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

– ‘What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why’, Edna St Vincent Millay

There is a Filofax belonging to Albert Adams which resides in the archive of the University of Salford Art Collection. Adams purchased the Filofax in 1986 and it seems to have remained in use by the artist for at least a decade. In amongst the home addresses for an international circle of friends – Brisbane, Preston, Johannesburg, Bombay, Alicante and Devon in just a page or two – and his London restaurants of choice, from Gujarati to Chinese, Brick Lane to New Oxford Street – there is an Edna St Vincent Millay poem that has been written out by Albert in longhand. I’ve quoted from it above.

I delve into the Filofax hoping to encounter something intimate and revealing, and honestly, hopefully, something gay. I wonder if his personal materials might offer a queer aspect to works that at first glance seem to say little about sexuality or gender or desire. What are we looking for, exactly, when we are looking for something queer anyway, either in a Filofax or in a body of work? And why? The word ‘lads’ makes itself known abruptly in Millay’s poem, reproduced in full in Albert’s handwriting. What goes through his mind when he is writing ‘unremembered lads’? Does he have any of his own? In Albert’s decade of bound leather, there is sometimes a man’s first name with no address or surname, only a phone number. Ask any gay man who he thinks those men might be. Then there is the occasional man’s name that has been crossed out. Entered, and then crossed out, sometime between the mid-80s to the mid-90s, in a gay man’s address book, in London. Ask a gay man what he thinks might have happened to those men. (It’s worth saying that the campest thing in the Filofax is the presence of Valerie Singleton’s home address, by the way.)

These things are only traces. They represent what I call ‘yearning’ – the desire to be connected to our queer forebears. I explore these kinds of things in my fiction, but perhaps it’s better for us to consider a different and broader picture in a queer placement of Albert Adams’ practice. For one thing, his long-term partnership with Ted Glennon is the reason we have access to the work in the first place. The fact of Adams’ romantic and sexual life is already a frame through which I have had access his art. I find this touching, as I find the relocation of his work from London to Salford pleasing. London usually gets everything, and it costs nothing to Albert’s work to house it in Salford. It’s not anchored to place in that way. That’s not to say Adams himself is placeless, only that his work holds a strong meaning through and beyond geography – it is British art, migrant art, South African, South Asian, global majority, post-colonial, diasporic, exilic work. It is also European art, and formally trained art, it is of its time and sometimes strangely timeless.

And is it also gay art? Queer art? The position of Adams as political subject must also include his marginalised sexuality. I reflect that even if he is not exactly in exile as such from South Africa while he is painting, he has rejected its white supremacy and its attempted denigration of his mixed ancestry, besides the fact that all queer subjects have existed in some state of exile from their heteronormative societies. The political affiliations of the queer subject are fluid because our adherence to the status quo is deliberately tentative and troubled/troubling. Adams is also a terrific stylist and technician who loves exploring new skills, and his influences are broad and very apparent. Is this magpie-like manoeuvring between schools and styles a queer thing? As in, outsider? As in, a non-adherence? As in, anything you can do I can do better? The works in Adams catalogue that we think of as Expressionist seem able to both collapse and splinter identity and we have seen how restless and rigorous was Adams’ reproduction of his own face, his own body as a subject. Gender and sexuality are maybe a distraction. More interesting is this sense of multiplicity in Adams’ work, of style and point of view and influence. Something non-normative that defies the white gaze (or even gays…)

Monkey on your back

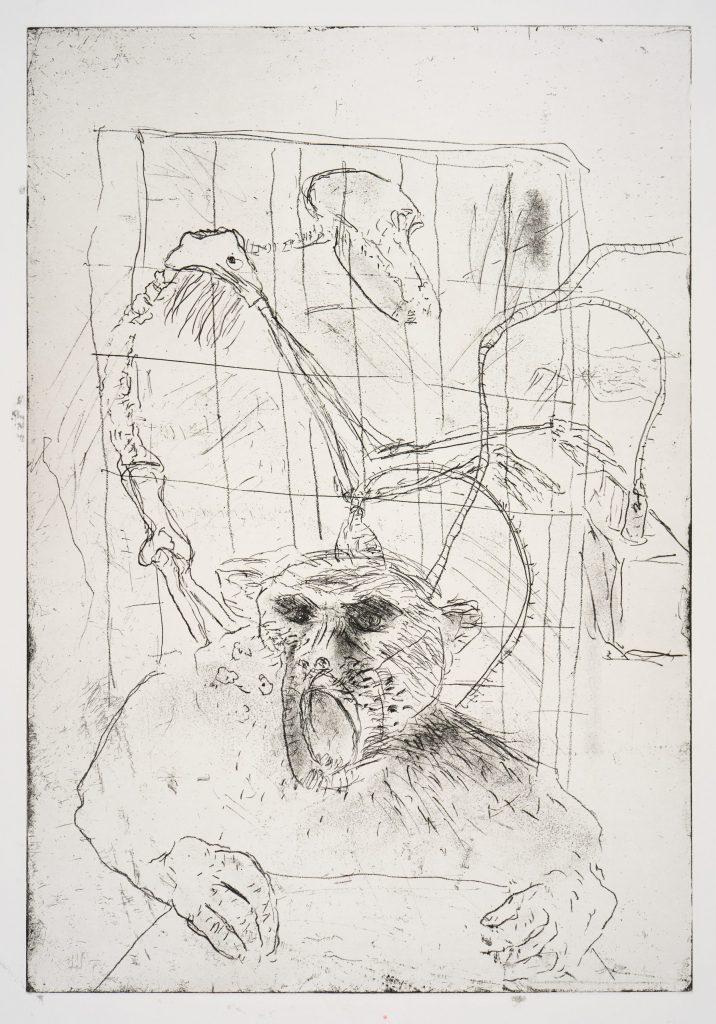

A faintly ludicrous Sherlock Holmes story, ‘The Adventure of the Creeping Man’, tells the tale of an ageing man with a much younger fiancée who succumbs to quack science in a bid to regain some youthful invigoration for his forthcoming marriage. His method is to ingest drugs derived from the bodies of primates. The unfortunate side-effects include walking around on his knuckles, scaring pets, and shimmying up the ivy at the side of his house in the dead of night. In the illustrated Conan Doyle book of my childhood, the image accompanying this story was a kind of hideous gothic chimera of the old man in full-on monkey-mode, hunched and screaming upon being discovered by Holmes and Watson. This is the image that came roaring up from my subconscious on first seeing Albert Adams series of primate images. What is the ape doing here?

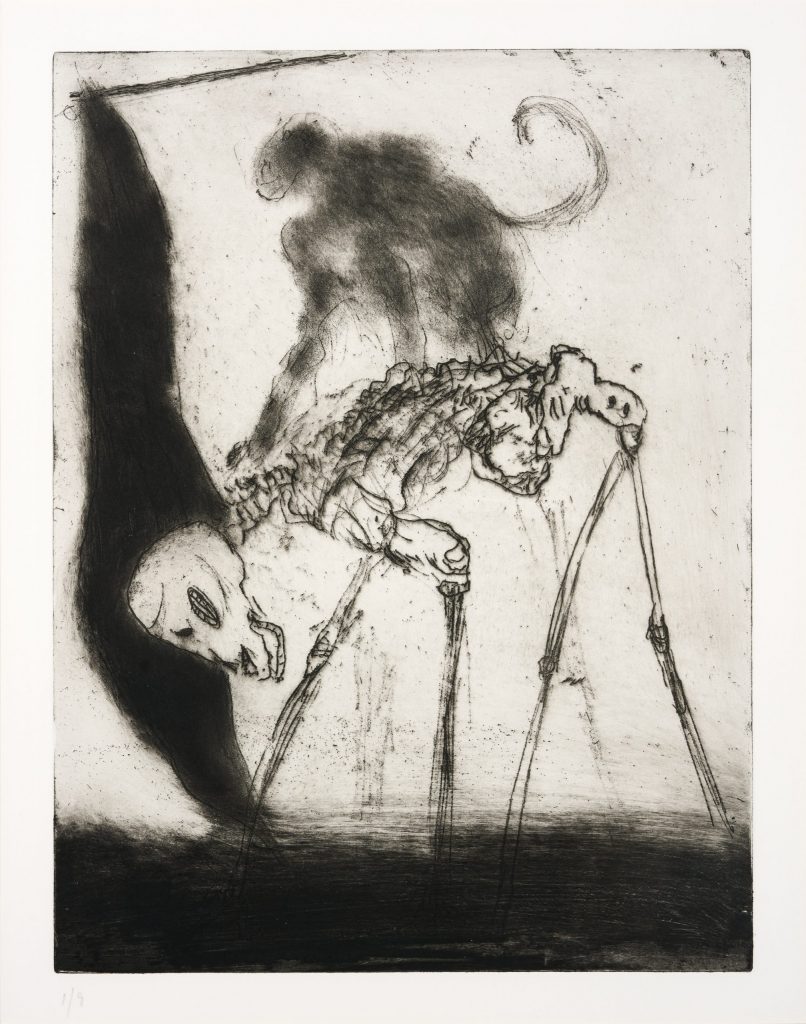

Adams’ ape most likely has its origins in the childhood stuffed toy that he brought with him from South Africa to England, and which now lives, somewhat forlornly, in the archives at The University of Salford Art Collection. In Conan Doyle’s story, the primate influence inside the old man represents the lust that he hopes to revive for his new marriage. And Adams ape? It seems to shapeshift and hold multiple meanings. In ‘Ape’ (2004) the stuffed toy has been touchingly reanimated into life, long-faced, and lovingly rendered, if unfinished, with dozens of fur-like strokes, benign and likeable. But it doesn’t remain tamed. ‘Ape with a Flag on a Skeletal Figure’, produced in the same year, sees the beast riding on another creature’s back as if in a victorious death march, with a black flag held aloft, its fur a kind of wild furze, while its beast of burden is an unidentifiable four-legged living skeleton.

These ghoulish roles are then reversed for ‘Skeleton Electrocuting An Ape’, an etching that images precisely that title, the sinister twist being that the skeleton also appears to be a post-mortem ape, animated in death, and conducting some kind of hideous painful experiment on the screaming ape, its living relative. Is the ape our metaphor, our other? The cruelty it conducts is recognisably a human endeavour, so why would any metaphor be necessary? Look again at the suffering monkey’s face too and it may itself seem more human than you first thought. What is going on in these diabolical constructs? The commentary is perverse and discomfiting. Is it about racism and/or violence, animal experimentation, or is it an accompaniment to Adams’ ongoing nightmarish imagery of carceral suffering?

This latter seems more possible when we encounter ‘Ape on a skeletal figure: Darfur’ in which the skeletal figure bears an ape upon its back that seems to be composed of only shadows. Is it a cruel spirit? Again the black flag of death billows ahead. An ape in art is often shorthand for a kind of malcontent spirit, engaged in anything from simple trouble-making to evil intentions. The stripping-down to a skeleton draws ape and man closer together, we see ourselves more clearly in one another at the level of bone. Placing our own evil outside ourselves and into the body of the ape is a diversion. What the ape represents can always be us, the old, uncivilised portion of the brain that not only bonds and breeds, but kills and screams in the forest at night. These images seem to emerge from the very back of the mind, like Conan Doyle’s monkey-man did for me. They are troublesome, and by the time they take their place in ‘Ape on a standing man’, they are seemingly the ones in charge.

Greg Thorpe is a writer, curator and creative producer. His art writing has appeared in On Curating, FRUIT, Feast, Double Negative, Artist Newsletter and The Fourdrinier. He has written about art for the Whitworth Gallery, Manchester Art Gallery, HOME Manchester, and Salford Museum & Art Gallery. His fiction has appeared in Best British Short Stories, Foglifter and Ellipsis. He works for Islington Mill, an independent artist community in Salford, and is currently Festival Director for GAZE International LGBTQ+ Film Festival. He divides his time between Dublin and Todmorden.

The University of Salford Art collection holds a substantial collection of Albert Adams’ work and archives, acquired with the support of the Art Fund and made possible by the generosity of Edward Glennon.

Albert Adams: In Context is supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and by a donor funded Salford Advantage Grant.

Further Reading:

Harold Riley, Albert Adams: Notes about a Friend, 2017, The Riley Archive.

‘Albert Adams: In Context’, symposium resources, 2022.

Greg Thorpe, From South Africa to the Slade: repositioning Albert Adams, 2022, Art UK.