Courtesy of Sam Parker

As a part of Between the Earth and the Sky our team assistant Sam Parker conducted a Q&A session with artist Alex Nelu to better understand his practice and thought process. As part of Arts Council England’s Developing Your Creative Practice grant, Nelu has continued to explore how to make a photographic practice more sustainable in multiple ways; like using photographing digitally rather than using harmful chemicals in a darkroom. Alongside this Nelu shares more information about his background and influences as an artist.

Find out more below.

You can also find more of Nelu’s work on his website here :

https://www.alexnelu.com/

Your Process

Starting off with a simple one; what equipment do you use? Be it cameras, scanners, other pieces of kit – what’s your go-to equipment bag got inside it?

“I prefer equipment that is lightweight and intuitive, something I can carry comfortably on long walks without it becoming a burden. Cameras are overloaded with menus and settings these days and I don’t enjoy wasting time when I’m out and about. Photography for me is about being present in the landscape, not buried in a screen.

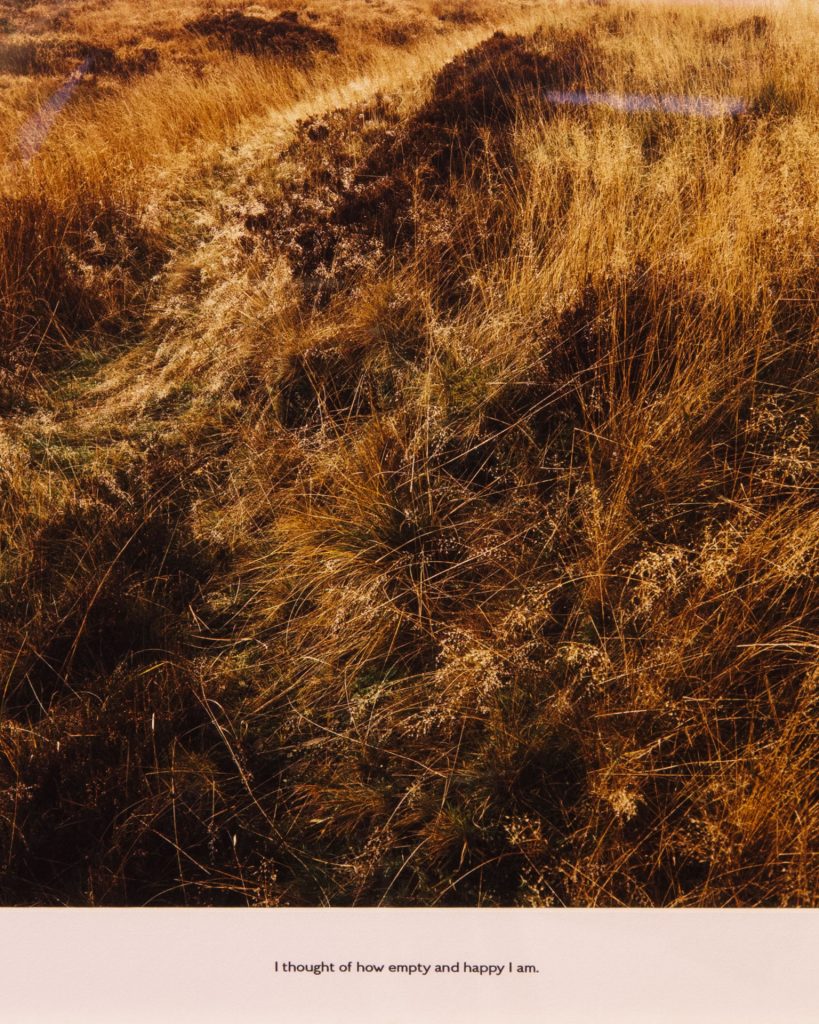

For ‘the wind was blowing as I was walking on marshy ground’, I bought a second hand digital medium format camera which allowed me to capture the detail and depth I was after. The images were printed digitally on a bamboo-based paper, then presented in frames borrowed from the Art Collection, as part of ongoing efforts to test more sustainable approaches in my practice.

In the past I loved working using basic film cameras, either point-and-shoot or SLRs. I prefer to stay clear from any AI features and try to avoid getting lost in technical specs as that often feels very disconnected from the actual act of making images.”

Courtesy of the artist

I know you’re accustomed to all sorts of processes and methods of producing imagery, so when it comes to Analogue or Digital media, which do you prefer?

“I love analogue photography and worked mostly on film for over a decade. But last year I challenged myself to try a digital workflow, purely because analogue seemed quite unsustainable, especially from my perspective as someone who was working mostly in colour. From the silver and gelatine in the film to the chemistry used in darkroom processing, there’s an obvious environmental impact there. That said, I’m also learning more about the hidden impact of digital, from the mining of rare metals for cameras to the energy-intensive nature of post-production workflows or cloud storage. Neither medium is better than the other in this regard as both come with their own issues, so I am keen to look into this more.

I do miss shooting film, and I’m not ready to part with it forever, that’s for sure. Many artists and creative researchers are actively working on ways to reduce the environmental impact of analogue practice, and I’m keen to see where that leads.”

the wind was blowing as I was walking on marshy ground (2024)

Archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

You’re images are always really well put together visually and lead the viewer to think more about the content within the work. How do you approach composition and storytelling within your photographs?

“Stephen Shore suggested that composition is about rearranging the three-dimensional world so it becomes interesting in two dimensions, and I relate to that. Photographic composition can be like solving an equation with multiple variables, and the challenge is to find a balance in the frame; but unlike maths the answer can be very subjective.

When I started studying photography 16 years ago, we had a module on cinema that introduced me to great films. As a teenager, cinematography certainly had a massive impact on me. Films like Paris, Texas, Meek’s Cutoff, and Red Desert still draw me back just for their visuals. I think it’s very important to train your eye by engaging with strong visual references early on and to work on developing an instinct for what makes an image compelling.

As for storytelling in photography, it’s quite different from cinema. You don’t have the same means to guide a narrative, so you work with much less, but to me that’s the beauty of it. Photobooks and exhibitions can function a bit more like films as the artist imposes a sequence, but photography is more suggestive. I love that it leaves space for interpretation to the viewer. I hope my work might allow others to bring their own emotions or experiences into it.

What I’m showing in ‘Between the Earth and the Sky’ is very personal, and it was a bit of a struggle to build the confidence to present it in this shape. Stephanie Fletcher’s input, the curator of the show, made a great difference as they were very supportive from the beginning, and I’m delighted that it’s out there like this.”

As artists we know that unexpected things pop up during the creative process – are there any technical challenges that you frequently face? And how do you overcome them?

“Of course, don’t we all! I sometimes end up on obscure, niche photographic forums trying to solve a problem, but I’ve learned to embrace the challenges rather than search for answers. They can become part of the work itself, whether it’s issues with equipment or process. I rarely set off with a rigid plan or chasing a specific, expected result; that sounds pretty boring to me so I will leave plenty of room for accidents to shape the work.”

Following that then, how big of a role is experimentation in your practice?

Courtesy of Sam Parker

“I guess experimentation sometimes starts with the technical challenges I mentioned above. Often an unexpected accident can open a new path. I like making beautiful images but I’m not really interested in chasing perfection. I’d rather accept and respond to what happens along the way and I believe somehow this approach also ties into finding a more sustainable balance.

Instead of discarding or spending time forcing something, I am actively trying to work with what I have, adapting or rethinking methods, which might reduce waste or energy use. Whether it’s testing techniques or materials, reconsidering workflows, or even letting limitations guide choices, experimentation is fundamental in photographic practice.”

Through this continuous development that you infuse into your practice, how do you think your style has changed over time?

“This work I show in ‘Between the Earth and the Sky’ marks a bit of a jump both visually and thematically from what I’ve done before. Moving to a more rural setting four years ago has inevitably shaped my practice. I spent a lot of time mapping the area, researching its history, figuring out what resonated with me, and eventually learning to embrace its bleakness throughout the year. Alongside that, personal things that were happening my life last year inherently translated in the work, making it more introspective. Walking, observing, and photographing have become more than just a part of my creative process; it was clear that they were also go-to coping mechanisms, ways of working through difficult emotions. Without wanting to say much more, ‘the wind was blowing as I was walking on marshy ground’ is in many ways the product of all the above. The opportunity to exhibit came at the right moment, giving me a chance to pause, take a breath, reflect and reset.

Us photographers can be incredibly stubborn; we resist change, we like to hold on to what feels safe. Staying open to new ways of working and challenging ourselves is essential. I’ve been fortunate to have people around me who taught me to accept that, I very much welcome it nowadays.”

Courtesy of the artist.

As artists we’re always trying to improve our practices and how we do things – do you ever seek feedback on your work? And if so, how do you incorporate this feedback going forward?

“Even though I graduated 13 years ago, I still find showing my work in progress daunting. I’ve always been a quiet, shy person, which is why I picked up photography in the first place. It gave me a way to express things without having to explain them. That fear of not being able to articulate what I’m up to is still there and perhaps will always be, but I know how important it is to seek and accept feedback. You can probably work in isolation and make brilliant art, but I feel that sharing it with peers you trust will most likely at least help you get there faster, if not elevate it.

At the moment, I’m working with a few people as part of an Arts Council England Develop Your Creative Practice grant, so I’m slowly getting more comfortable with sharing work in progress and taking feedback on board. But even now, I still get a lump in my throat when it comes to it. That said, it’s been incredibly useful, and I am embracing it more. It’s quite funny because I am never one to shy away from giving feedback when asked.”

Many struggle with getting into the flow of making work as well as talking to others about it – do you have any tips or routines to get into a creative mindset?

“For me, it usually involves walking, browsing photobooks, even looking at old maps. These are the main things that allow my mind to wander. I also find that watching artist talks can be really inspiring. Even better when things don’t happen on a screen.

I also make notes whenever an idea comes up, and I often revisit them, writing them down properly to see if they’re worth pursuing. In my experience, even the smallest snippet can grow into something.

Ultimately, I’d say the key is to find a productive space or workflow where you can focus on your ideas and see what works for you.”

Speaking on creative process – which part of your creative process is your favourite?

“I enjoy being out, that’s the best part for me, and I feel lucky that’s one of the main components of my creative process. For me and many others, photography is about being outside, walking, observing, and responding to a place even in questionable weather.

My least favourite is being in front of a computer but that’s still necessary unfortunately, even though I am seeking new ways to streamline and shorten that, both for my own sanity and to use less energy.”

Your Practice

Courtesy of Sam Parker.

We’ve mentioned sustainability a few times already, but how big of a role is sustainability in your practice? And how have you implemented it?

“I’ll admit, I didn’t think much about sustainability until a few years ago when Lizzie King and Gwen Riley Jones ran an amazing programme of workshops and talks at Salford called ‘Sustaining Photography’, supported by the Art Collection and the Sustainability Team. I was already mindful of some things such as trying to produce less waste or buying second-hand equipment, but it made me realise the broader environmental impact of photography. It was a good wake up call.

Right now, I’m testing new approaches as part of a year-long grant on developing a more sustainable photographic practice. I have a sustainability statement on my website outlining the steps I’m currently taking, which I update as I learn more. I believe in being transparent about any positive changes I make, so others can apply or challenge them. Small adjustments across a wider community can add up to a significant positive impact, especially nowadays when we became so desensitized to snapping images on our phones without giving too much consideration to what happens to them afterwards.

Hopefully, I’ll find a carbon-neutral way to publish and distribute my findings next year, but for now, I’m happy to learn more and open conversations, especially in my front facing role at Salford as a Creative Technical Demonstrator. Even if the students might find it annoying sometimes, hopefully, it plants a seed.

Alongside Lizzie King and other academics, I am one of the founding members of the Sustainable Arts Practice Research Group (SAP) in SAMCT, so I actively contribute to interdisciplinary discussions and initiatives aimed at integrating eco-friendly practices within art and design curriculum. Our focus is on reducing environmental impact, promoting sustainability in artistic production, and fostering a culture of ecological responsibility within the academic and creative community.”

Working in this more sustainability focused way, have there been any big shocks in the way you’ve had to change your methods and processes?

“Well, stopping film photography for a bit was painful. At first, I overcompensated by taking too many pictures, something us photographers are guilty of, chasing that fear of missing out. But I started to feel guilty very quickly and finding that balance was so important.

I also had to change the software I was very familiar with, to move away from saving unnecessary duplicates of the same image. Old habits die hard, so it’s been a challenge, but I feel like I’m getting there. Making sustainable choices isn’t always easy, but simple things will make a difference.”

Răzvan Mazilu – Theatre Director/Choreographer/Performer

Client – C4US Magazine

Courtesy of the artist.

Aside from sustainability, do you think your personal identity or background influences your work? If so, how?

“Everything I put out there is shaped by who I am, where I come from, and where I find myself now. Even though I’m now British, I still feel more Romanian as I lived there far longer than I’ve lived here. That immigrant identity remains a big part of me. It’s probably why nostalgia runs through my work. Perhaps photography for me is a way of processing that sort of emotion, the longing for a place, time or feeling. I often find myself looking for traces of familiarity in an unfamiliar landscape and it’s something I’m drawn to involuntarily. In that way, I think my identity is always present in my work, even if it’s not too explicit.

In my previous life as I often call the time before moving to the UK, I worked as a freelance photographer and a studio assistant, both fast-paced roles that equipped me with some resilience and gave me a strong technical foundation. Commercial work wasn’t always enjoyable, especially with the pressure you feel when you’re doing it in your early twenties. But looking back I’m very grateful for the experience and it equipped me with incredible skills that continue to inform my practice today, that’s for sure.”

Are there any other artists, practitioners, or themes that inspire and influence your practice?

“I was taught by Nicu Ilfoveanu during my BA, whose work is very influential to many Romanian landscape photographers, myself included. When I first moved to the UK, I was fortunate to meet Lizzie King and Craig Tattersall, both incredibly creative and prolific artists.

I frequently revisit the work of Robert Adams, his photography but also for his writing. I’m also always drawn to the photography of Tanya Marcuse, Stephen Gill, Vanessa Winship and Alessandra Sanguinetti. More recently, I’ve discovered Laurie Brown and John Pfahl.

Since my work is rooted in exploring landscape, its historical context, and how we perceive it, Patrick Keiller has been a significant influence. His Robinson films and The View from the Train, which I read just before the pandemic, influenced my perspective on the intersections of geography, history and narrative.

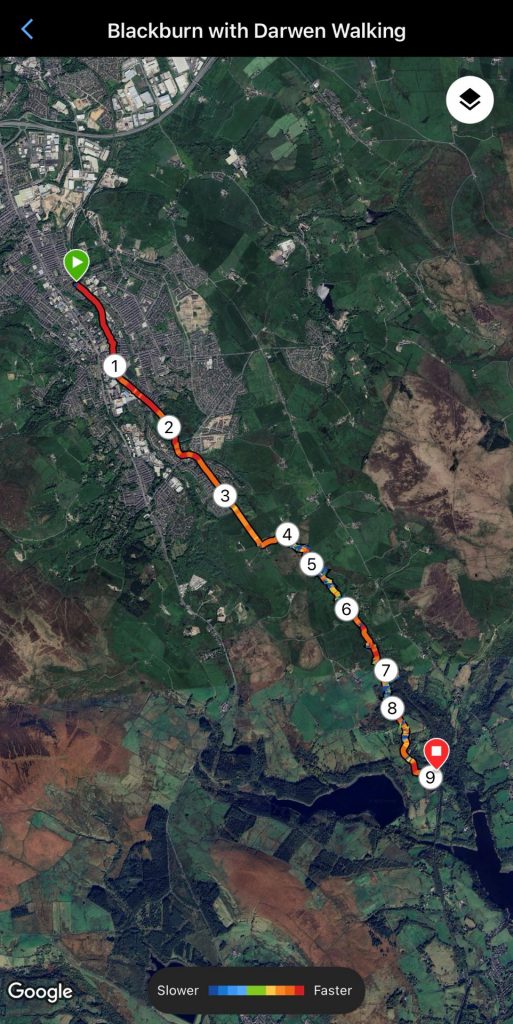

I find that the outdoor environment itself can help map an emotional landscape. The West Pennine Moors have amazing colours in every season, and even at their bleakest moments, I find it hard not to enjoy being there. The themes I’ve been approaching for this are very personal: dealing with solitude, displacement and adapting to an unfamiliar place, but in a way the work is perhaps about embracing these emotions. By visiting spaces that hold past histories of their own such as disused quarries, reservoirs or the path that was once a Roman road, I contemplate and confront my own journey of relocation and adaptation. There’s just something about walking up there and facing the darkness head-on, like a ritual that becomes part of the work itself.”

How do you start a new project? Is there an extensive plan or do you just begin and roll with what comes?

Courtesy of Sam Parker.

“I wouldn’t say I start with an extensive plan. If anything, the structure usually takes shape after I’ve already started. My projects usually evolve from something I’m already doing, whether that’s walking, researching, or just following a feeling that something is worth exploring further. If ideas linger in my mind, I try to pursue them and see where that takes me.

This project grew out of the time I spent on the moors after moving here in 2021. It was still very much a pandemic, and I think we all became more aware of how much we rely on being outside when we had to stay in. For me personally, that shift was quite significant, not just in terms of appreciating the landscape but in understanding how being out there affected me emotionally. I started observing, mapping and photographing, and that slowly morphed into a project rather than something I deliberately set out to make.”

Are there any dream projects or collaborations you’d love to pursue in future?

“I’d love to work with other people who have a deep connection to landscape, whether that’s artists, writers, researchers or the local community. I’m particularly interested in long-term projects that allow for a slow, considered engagement with a place-based subject and multiple angles and contributions would only enrich the work. I think I would also enjoy being an artist in residence somewhere with a layered history, I love sites that invites exploration and reinterpretation, whether natural or man-made. Hopefully, I can also find sustainable ways to engage with the communities that inhabit it and make a positive contribution.”

Thinking about the future – how do you see your work evolving in the next few years?

“While my work is deeply personal, I’m interested in expanding my engagement with others through collaborations, residencies, or conversations that bring new perspectives into my process. I can also see my practice becoming more research-driven, perhaps incorporating more data, either historical or scientific while still being quite personal. I imagine my work will continue to explore similar themes, but I hope to find ways to refine my approach, both in terms of sustainability and how I communicate these ideas visually.”

Courtesy of Sam Parker.

Plenty of students and other early career artists all want to know how artists they look up to would advise on beginning a career – so, what advice would you give to someone starting out in your field?

“Keep taking pictures every day, it’s the best way to improve. Go see art and artist talks as often as you can. Watch good films. If you’re a student, spend time in the library’s photobook section; if not, visit a bookshop or the local library. Don’t get caught up chasing the best equipment, you don’t need it. Find something that works for you and focus on making work, not collecting gear. It can be a difficult, competitive field so please remember to pause sometimes, take a breath, and remind yourself why you’re doing it. Your work should make you happy and bring you fulfilment, don’t try to please others and don’t let them dictate what your photography should look like or be about. And please try to be mindful about the environmental impact of your work and see if there’s any changes you can make as there might be plenty of actions you can take without compromising your artistic vision or process.”

And finally, the big one – do you think art, and by extension photography, has a specific role in shaping society?

“100%. Photography is such a powerful medium and I believe that studying photography is important, not just for the technical skills but as a way to understand its historical and political impact. While photojournalism can be the most obvious example, documentary and conceptual photography have also been instrumental in questioning structures of power and shifting cultural perspectives. Socially engaged photography is another crucial area where the medium can have a direct impact on communities. Projects that involve collaboration with participants rather than just documentation can empower individuals and challenge narratives.”

Courtesy of Sam Parker