As part of my role as Team Assistant I was very lucky to get the chance to go on a research day visiting art galleries around Manchester. It’s always brilliant to be reminded of the strength of Greater Manchester’s cultural scene, and it was insightful to see what innovation can be brought to our own collection.

Smooth Sailing

ESEA Contemporary

My rainy December trek through Manchester first brought me to ESEA Contemporary to see Marcos Kueh’s Smooth Sailing, an exhibition curated by Jo-Lene Ong, which explores areas such as cross-cultural histories, diasporic identity and collective memory.

The first piece on display is Three Contemporary Prosperities (2025), in which three large tapestries depict the traditional Chinese deities Fú 福 (Fortune), Lù 祿 (Prosperity), Shòu 壽(Longevity) as contemporary idols: a billionaire, celebrity and immortal elder. This piece is a continuous and evolving work with previous iterations being a millionaire and influencer and demonstrates humanity’s insatiable ambition and desire. Hanging in the doorway to the main exhibition space is Kueh’s Woven Poster: Spirit of Labour (2025). I was surprised by how instantly my mind was thrown back to the labour union posters and certificates in the Peoples History Museum where Kueh had a residency for his research. These motifs alongside traditional Chinese imagery point to the thread of exploitation and labour injustices that runs through both Manchester and Hong Kong and their industries.

Industrial weaving with recycled polyethylene terephthalate threads, wood, rope, sandbags. Photography: Keira Marchant.

Pushing past this tapestry, on entry to the main exhibition space, I couldn’t help but find my eyes drawing instantly to Abandonment (2025)- a colossal wreck of a ship’s mast draped in an opulent weaving (made from recycled threads!).

In greens, golds and blues, Chinese Gods fight violent wars. In an accompanying audio piece by the artist, Kueh considers his grandfather, a man displaced by Japanese occupation and forced to move to Borneo.

Had the Gods he prayed to abandoned him? Were they fighting against him? Or is he collateral damage in something larger than himself?

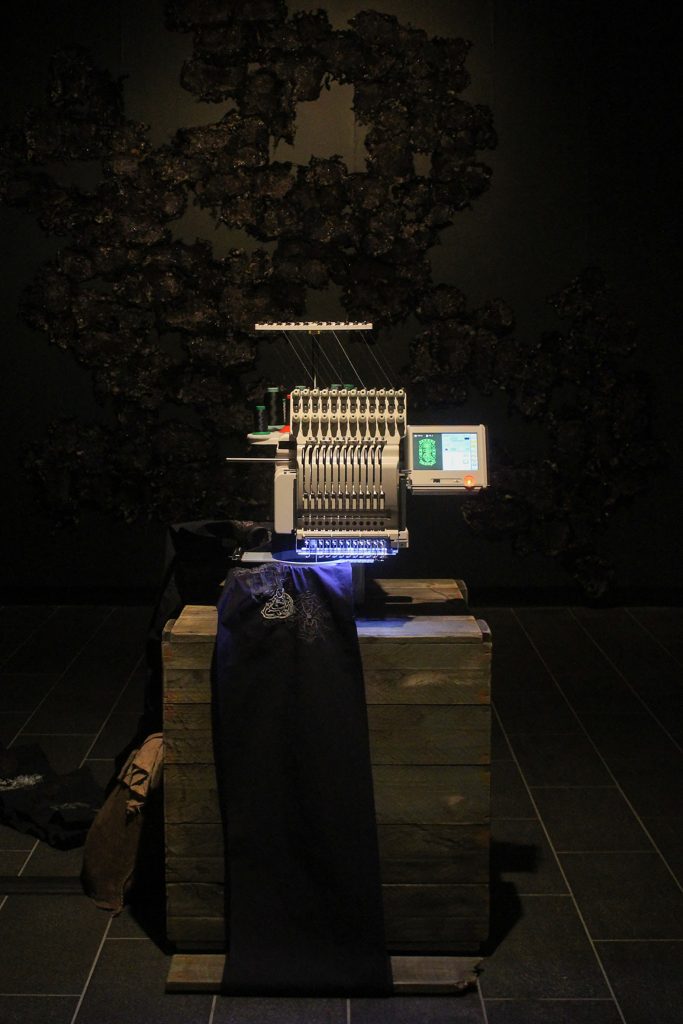

Rhythmic whirring behind me eventually encouraged me to peel my eyes away from Abandonment, and to look at Love, Labour, Loneliness (2025), a little automated embroidery machine ceaselessly embellishing of a long trail of fabric, which sticks out like a tail of the machines own making.

To me the little machine working away in a darkened room, looking ahead as it pushes past one embroidered talisman onto the next, seemed somewhat anthropomorphic. It brings to mind the countless working hands that create the textiles that decorate our world, and the lives of the people behind them.

In Kueh’s Hope and Fear (2025) masses of thick warped deadstock fabric are pieced together with delicate embroidered talismans and vintage business logos giving well wishes such as ‘Big Happiness’ (a tradition that, much to my sadness, has gone out of fashion). This deadstock fabric, which would have otherwise been bound for the incinerator, gives a visual reminder for waste produced from industries such as textiles.

Roots in the Sky

Home

Next I stopped off at Home to see Roots in the Sky curated by Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, an exhibition which uses the common languages of figuration and abstraction to collect the experiences of the black diaspora across the globe, homing in on shared experiences and emotions that transcend geographical boundaries.

On entry to the exhibition I was faced with a collection of immersive works by Elena Njoabuzia Onwochel-Garcia. Here she creates a pastiche of allegories and myths in a reflection on the various histories that shape her heritage. In this group of paintings, the traditional Igbo associations with crocodiles as both and embodiment of deception and a guide to primal wisdom, are considered alongside reimagining of classical Greek figures such Prometheus who is reconsidered, not as a colonial force of ‘civilisation’ but as a symbol of black resistance.

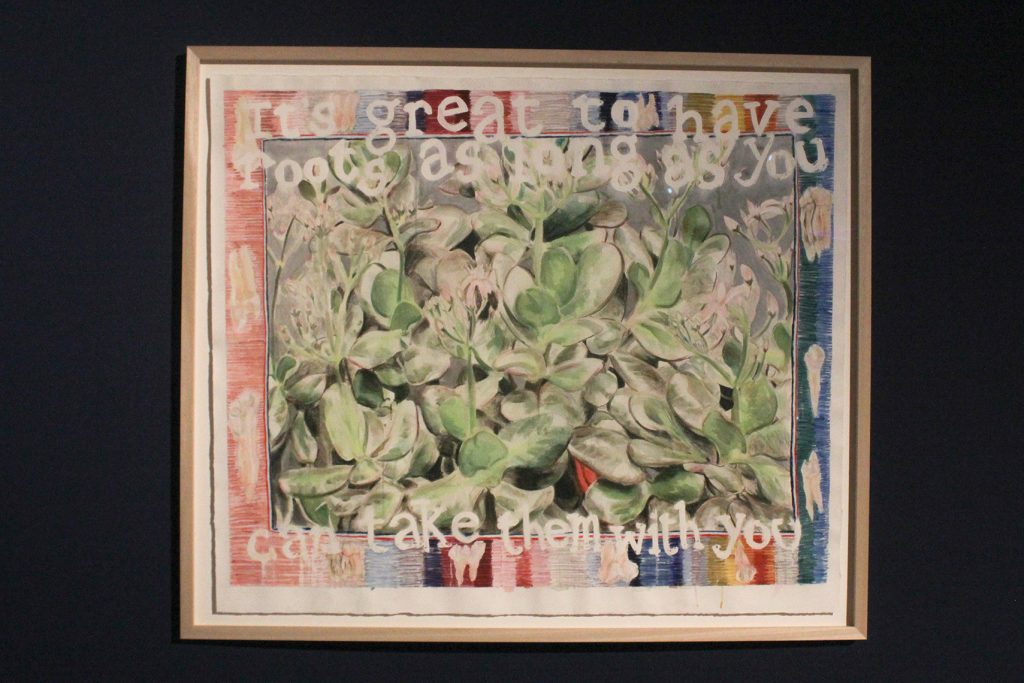

Jade de Montserrat’s It’s great to have roots as long as you can take them with you (2025) uses the jade plant (sometimes called a lucky plant or money plant), a plant able to root without soil, alongside English regimental medal ribbon, to draw associations between the uprooting caused by British imperialism and the effects still felt by diasporic communities today. I felt that this piece acted as an important central point to the exhibition which draws together individuals displaced by the violent acts of the past, through their common threads of experience, which they express so powerfully through art.

The interconnectivity of the works in this exhibition, combined with the variety of voices, perspectives and contexts which bounced around the wide open gallery space, made it a brilliant experience to walk through. An experience which was improved by accessibility materials such as easy read guides which help open the exhibit up to more people.

It Requires Getting Lost

Castlefield Gallery

At Castlefield, in partnership with Roberts Institute of Art (RIA) and Venture Arts, is It Requires Getting Lost. In an innovative approach to curation, Castlefield has three artists working to create pieces in dialogue with each other and in response to pieces from the David and Indrė Roberts Collection, all centring around the human relationship with nature.

Castlefield itself feels almost cavernous and subterranean in nature, and with the soundtrack echoing from Gregory Herbert’s video piece Well Wishing – Wishing Well (2025) and light dancing around the space from Malik Jama’s Cave on the wall (2025), the descent into the gallery area is an experience in itself.

The pieces in the exhibition, although often miles apart in terms of mediums are cohesive in their message. Jocelyn McGregor’s performance sculpture Karst Window (2025) places people at the will of the earth, they are incorporated into the earths cycle and perform their part in helping water along its journey through waterfalls and streams. It is a refreshing take when the planet is often considered to be at the mercy of humans who have dominion over it.

At their core each work points towards the strain humans endure in their persistence to find answers within nature, a strain that in the end will amount to nothing. They instead offer the alternative of accepting nature as it is.

The Beginning of Knowledge

Whitworth Art Gallery

My final stop was Whitworth Art Gallery‘s exhibition, The Beginning of Knowledge. Using natural dyes on llanchama (a cloth made from bark), Santiago Yahuarcani, leader of the Aimeni (White Heron) clan of the Uitoto people, explores the relationship between his ancestors and the universe. This exhibition displays works from the past 15 years of Yahuarcani’s career in sections backed by audio of rainforests and people speaking Uitoto and Spanish.

The first section I was met with consisted of larger works, one of these being El Mundo Del Agua (Water World). For the Uitoto, the world is made from three parts the Sky world, the Ground world and the Water world. The Water world is defended by pink river dolphins, who are considered symbols against destructive forces that threaten the Amazon. The figures in this painting blur the lines between human and animal and instead challenge us to consider both as souls of the same universe. These monumental pieces are an impactful introduction into the beliefs and oral histories that bound Yahuarcani’s ancestors to the world in which they made their lives.

Throughout The Beginning of Knowledge you gain a sense of the significance of spiritual connection within the Uitoto culture, as well as the resilience of those who continue to share their histories and beliefs both as an act of defiance to destructive external forces, and an act of grounding future generations in tradition. Thematic sub sections such as Spirit World, Origins of the Universe, Guardians of the Amazon, and Sacred Plants work together to produce an expansive depiction of the rich majesty held in the oral histories of the Uitoto, from the animals which embody the souls of the dead, to the tobacco and ayahuasca which act as teachers and a spiritual conduits.

On turning into the section titled The Time of the Weeping of Blood there are new creatures introduced, creatures with all purity removed, and different scenes, which starkly contrast the well-balanced cycle of life and death that acts as a central point in the Uitoto’s coexistence with their environment. These scenes depict the acts of unimaginable cruelty carried out against indigenous communities during the Putumayo Genocide (1879-1912) in the name of greed and material wealth. In these paintings, imagery of fire, writhing figures, monstrous beings and white tears resembling the rubber which communities were exploited for, dominate. The tranquillity of the water world seems worlds away from this section of the exhibit, separated from us by a crevasse that extends deep into a pit of human greed.

The deep psychological wounds left by imperialism and industry, are discussed by Yahuarcani and his family in El Canto De Las Mariposas (The Song of the Butterflies). Here it is mentioned that the souls of those lost through the violence of the rubber boom live on as butterflies and protectors of the rainforest in which they were born. This film paints a picture of the resilience and hope that is needed for the tackling of modern issues today. It also presents to us the potency of spiritual beliefs and revere for nature in the peaceful combat against environmental devastation and cultural oppression.

The galleries and exhibitions visited in my trip were an amazing reflection of the vibrancy and variety of culture in Greater Manchester, they also demonstrated that modernity and new ways of thinking are being embraced across all sizes of institutions. However, what I found most interesting was that, even though subject matter was often very different in each place, they all tapped into similar common themes and sought to understand the place of humans and nature within a global landscape that has shifted completely through colonialism and industry.

I am so grateful to have been given the chance to take this day to explore. And would like to say thank you to all the organisations mentioned and their helpful staff, and to Jo-Lene Ong for taking time to walk me through the exhibition at ESEA.

by Keira Marchant (Team Assistant)