Early in Spring 2020, the University was successful in a small grant application to The Paul Mellon Centre for the Study of British Art, for research into South African artist Albert Adams (1929 – 2006).

Adams, who was of African and Indian heritage, was denied access to formal education due to apartheid policy. He moved to the UK in the 1950s, where he continued to live, study and teach until his death in 2006. Much of his work focused on political oppression, abuse of power, and personal identity.

The University holds one of the most significant archives of Adam’s work, including prints, drawings, paintings and studio artefacts. The collection was acquired with Art Fund support in 2012 and made possible with the generosity of Adams’ surviving partner, Edward Glennon. You can read more about the collection here.

Research Fellow in Art History Dr Alice Correia, will host a study day on Adam’s work in Spring 2021 (post-poned from Summer 2020 due to Covid-19), and curate a new display in Albert Adams room – a permanent exhibition of Adam’s work, in a room renamed in his honour in 2015.

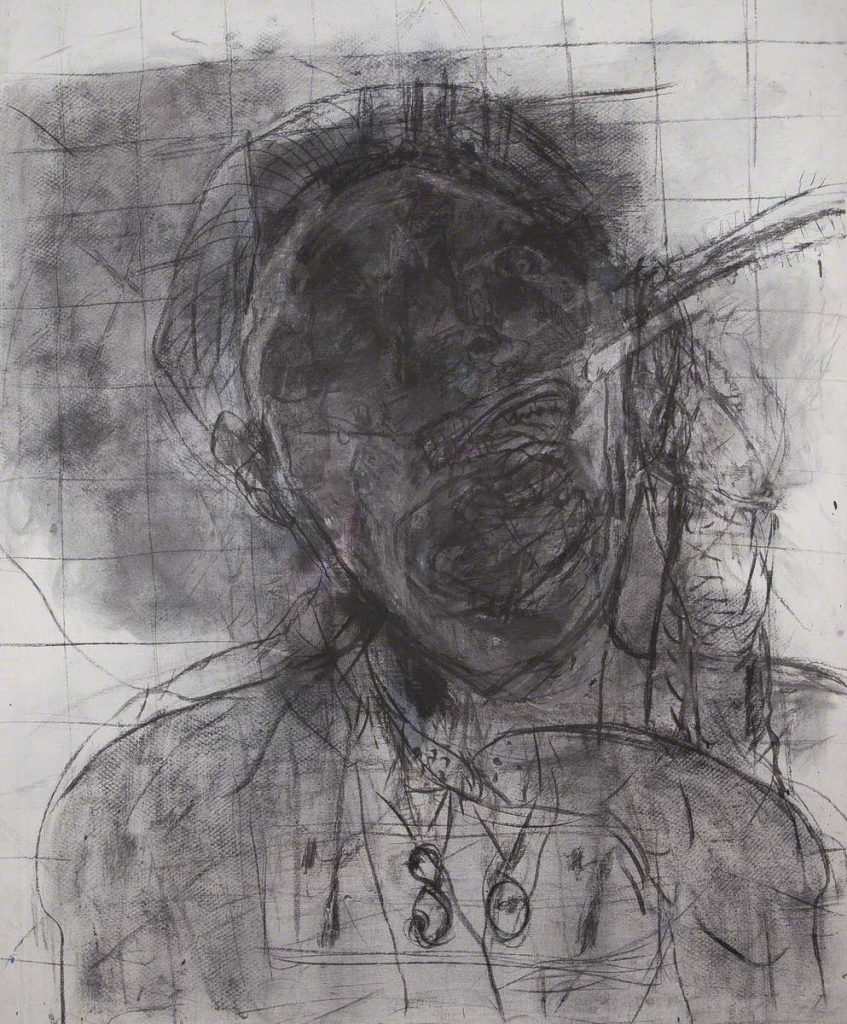

Here, Dr Correia reflects on one of Adams’ later drawings (Celebration Head, 2003, pictured) in light of the Black Lives Matter movement.

(c) The artist’s estate.

One of the art works by Albert Adams held in the University of Salford Art Collection is titled, Celebration Head, 2003. It is a large oil and charcoal drawing on canvas and depicts the head and shoulders of a male figure. Despite its title, the drawing is a mediation on suffering and pain. It is a powerful work, and looking at it in the summer of 2020, at a moment of global anti-racism protests, its relevance to current conversations about blackness and discrimination is considerable.

As part of his Celebration series, 2000-2002, Adams’ drawing can be placed within a larger body of work that addressed the subjugation of the black body in South African culture. Marilyn Martin (Director of Art Collections, Iziko Museums of Cape Town) explained that the Celebration series “referred to post-apartheid South Africa and the challenges, dangers and threats that came with political change”.i Although Adams had left his native South Africa to study at the Slade School of Art in 1953, and settled in Britain permanently in the early 1960s, the country and particularly the ways that it oppressed its black population through its apartheid laws, remained central to his work. A year before his death, in 2006, he wrote “My work is based on my experience of South Africa as a vast and terrifying prison, an experience which even now, after a decade of democracy, still haunts me”.ii In this context, Celebration Head seems to caution against too much celebration in the post-apartheid era. His work reminds us that the deep wounds and traumas experienced by generations cannot simply be celebrated away, that past atrocities continue to affect the present.

In Celebration Head, the man’s head angled in a jarring expression of pain. Although his facial features are smudged and obscured, it is clear that he is presented with two mouths, both of which are grinning in anguish, teeth bared. Around his neck is a plaque, with the number 7867. The number is reminiscent of prisoner numbers included in police mugshots, and as such becomes a sign of criminality, reinforcing a stereotype that casts black male bodies as threatening. In the disparity between the man’s suffering and his identification as criminal threat, as audience members we are asked to question our own prejudices. Although Adams’ drawing was created in response to a South African context, it could just as easily refer to black experiences closer to home: from the systemic anti-blackness found within our institutions including the police and government; the historic and continued framing of black people as criminal in the press; to the racist micro-aggressions that impact the daily lives of black people in Britain.

In March 1945 Pablo Picasso stated that, “painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war for attack and defence against the enemy”.iii Adams, it seems, was well aware of Picasso’s words,iv and Celebration Head is exemplary of his life-long commitment to engage with the painful inequalities and injustices at work in our global societies.

Dr Alice Correia, June 2020.

Albert Adams (b. 1929 Johannesburg, d. 2006 London) was painter and printmaker of mixed-raced (African/Indian) heritage. His triptych, South Africa, 1959, is considered by many to be one of the most important paintings in the history of twentieth century South African art. A selection of Adams’ work is on permanent display in the Albert Adams Room in The Old Fire Station, University of Salford.

A study day examining the work of Albert Adams will take place in Spring 2021, funded by The Paul Mellon Centre for the Study of British Art.

Black Lives Matter

Read more:

UOS Library – BLM Reading List

UOS Student’s Union – Statement

UOS Vice Chancellor – Statement

Endnotes:

i Marilyn Martin, in Albert Adams 23/6/1929-31/12/2006: A Tribute, p.6. Available at: https://adamsalbert.files.wordpress.com/2016/12/albert-adams-a-tribute.pdf , accessed 25 June 2020.

ii Albert Adams, as cited in Albert Adams 1930-2006; Press Release, Northumbria University Gallery, 2015.

iii Pablo Picasso, statement March 1945, in Herschel B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, Berkeley: Universityof California Press, 1968, p.487.

iv See Lorna and Graham de Smidt in Albert Adams 23/6/1929-31/12/2006: A Tribute, p.3, as above.