Assistant Curator Stephanie Fletcher reflects on her participation in Prof Beryl Graham’s one-week intensive course Curating after New Media:

Curating after New Media professional development short course – London, February 2019

In February 2019 I spent a brilliant and thought-provoking week with artists, curators, and creative producers for the Curating after New Media professional development course, organised by Professor Beryl Graham of CRUMB.

Together we asked about the possibilities and challenges of new media in galleries, museums and other art (and non-art) spaces; as well as more broadly addressing the shifting roles of the curator, the institution, the maker, and the audience today; through visits to a broad host of central London venues.

It’s impossible to summarise the breadth and depth of conversation and learning, but I have no doubt of some short and long term positive impacts to the way we develop and articulate the art collection at the University of Salford – in particular, our About the Digital strand.

With thanks to course leader Professor Beryl Graham, all curators/speakers – and the class of 2019!

Critical Making, Collaborating and Producing: how are new media & technologies changing our creative processes?

With Head of Programming John O’Shea at SPARE PARTS, the Science Gallery, we considered the shifting dynamics of artist practice today. Collaboration, consultation and communication between artists, designers, engineers, scientists, academics, technicians and communities becomes increasingly commonplace – allowing a fruitful sharing of skills, resources, knowledge – and equipment. Whilst allowing for more exciting and multi-layered outcomes, which may reach much wider audiences, these collaborations are not without risk: rapid developments in science and tech research can shift the whole concept/content/context of a work. O’Shea counteracts this with ‘reactive, adaptive and hybrid’ curating approaches, as well as importantly re-considering ‘failure’ as a necessary part of a research narrative; embracing projects which live, change, adapt, and have multiple possible iterations and outcomes.

Gareth Own Lloyd at Machines Room also considers the dynamics of critical making processes: asking who (socio-politically, economically or otherwise) can gain access to spaces, equipment and knowledge in the first place. Machines Room addresses this with flexible modes of participation: ‘time-bank’ models of working exchange hours volunteered for access to machines or materials; alongside mentoring projects, youth education, and encouragement of open-source software.

Marc Garrett at Furtherfield also emphasised democratic and community-led ways of working. The organisation, which has been at the forefront of new media culture for over twenty years, considers its approach as a kind of ‘continuation of the Fluxus movement through technology’. Decentralised and non-hierarchical structures of infrastructure, technology, community and play – such as the DIWO – Do-It-With-Others model – are used and advocated for.

Rather than falling into the trap of fetishizing new technology itself, Furtherfield are careful to utilise tech and media to ‘free up new ways to think and be’ – including ‘hacktivist’ projects which have potential for real social change – such as the SEFT1 hacked car.

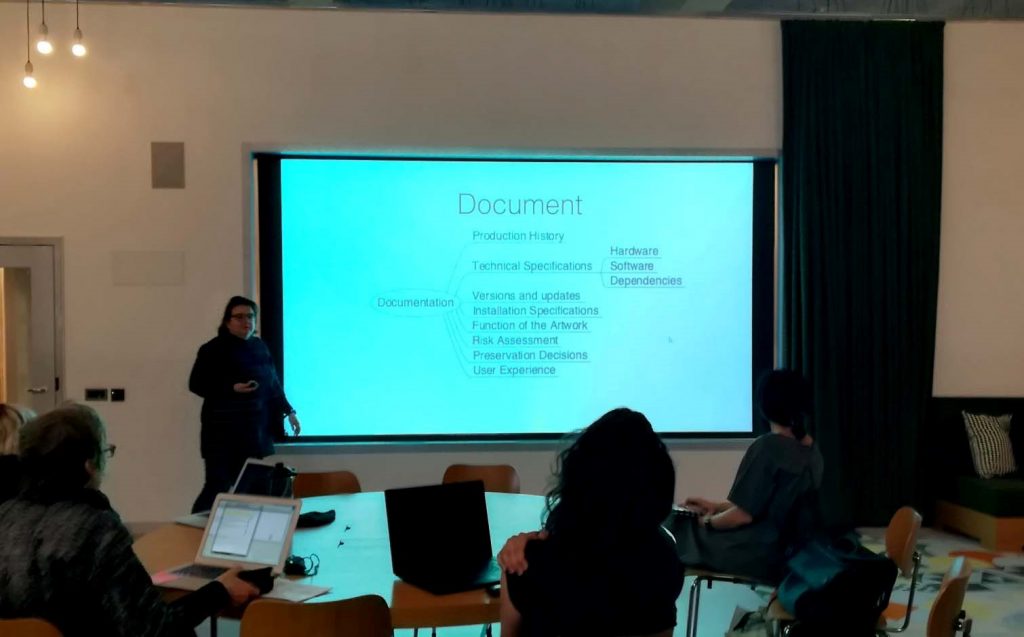

Collecting New Media Art: What are the challenges and emerging solutions for categorising, collecting, conserving documenting and re-displaying works in new media and digital technology?

As conserving and re-displaying new media art is an ever-evolving challenge for collection curators, it was fascinating to meet with time-based media conservator Patricia Falcao of Tate.Discussing examples including Michael Craig Martin’s Becoming, Rafael Lozano Hemmer’s Subtitled Public, and Jose Carlos Martinat Mendoza’s Brutalism; Patricia advocated for establishing a robust set of ‘significant properties’ essential to the display of the work, (see: Matters in Media Art) alongside a willingness to continually adapt, learn and customise conservation strategies to the needs of each work.

Amongst the group we also agreed a need to be resourceful, playful and collaborative – acknowledging that a good level of tech skills and a willingness to learn, experiment are increasingly essential to the curator’s role – or at least knowing enough to be able to find the right collaborators. Useful resources include: the Variable Media Network and the ZKM digital art conservation project – and not forgetting free YouTube tutorials for installation and tech tips!

At the V&A Collection with Douglas Dodds and Melanie Lenz, the ‘digital’ collection began with a number of digitally-made works on paper; with artists including George Nees and Manfred Mohr using algorithms and computing to generate geometric marks and patterns. It now includes born-digital works in software and video, and recently held a large scale exhibition exploring video games as art; each with individual challenges in care and display.

Most striking is their Rapid Response Collecting programme: an initiative which flips the usually slow process of museum acquisitions. Contemporary design objects deemed to “have been newsworthy…because they advance what design can do, or because they reveal truths about how we live” are quickly collected, even if they pose technological difficulties in future care and conservation. An e-cigarette, mobile phone, apps and games, drone, digital thermostat as well as toys, fashion and design items sit alongside perhaps their most complex acquisition: the social media platform WeChat.

Experiencing new media: What are the relationships and experiences between humans, art and technology now?

In a world of Big Data, curator Hannah Redler and art associate Julie Freeman of the Culture as Data programme at ODIchampion data itself as a contemporary art medium – rather than something to just be channelled into neat visualisation graphics. Manchester based Sam Meech translates collected data of working patterns into knitted banners; Thomson & Craighead source images from real-time online webcams to collate a ‘global electronic sundial’; and Pip Thornton contrasts the financial and emotional value of search engine terms with poetry.

The programme questions our personal and political relationships with the power of data; neatly summarised by Beryl’s borrowed portmanteau ‘crandy’ – a mixture of creepy and handy (think about your phone’s ability to suggest items to purchase nearby, based on your location, mood or recent habits and searches). With their main exhibitions installed in and around the working offices of the ODI, the programme also questions where and how often we encounter digital art, and what conversations or new research it might instigate.

All I know is what’s on the Internet at the Photographers’ Gallery urgently addresses the way we experience images in the Internet age, and the changing labour on both sides of image production and consumption. Human web content monitors and Google Street view photographers must capture and regulate internet images at an increasingly rapid pace, to feed an increasingly addicted, yet attention deficit, social media audience. Of course, I duly Instagrammed the show while I was there…

Whilst Autograph in Shoreditch – previously called Autograph ABP, the Association of Black Photographers – still include a media specificity (‘photography and film’) in their mission statement, Programme Manager Ali Eisa reminded us that a strong core ethic must run throughout creative practice, beyond any limits of medium or technology, which can rapidly shift in meaning, purpose and accessibility over time. The gallery has existed, in various forms, since 1988, to ‘explore identity, representation, human rights and social justice’. In any case, the gallery has found that most practising contemporary artists they work with rarely confine their practice to a single medium either – exemplified by the current exhibition The Space Between Things by Phoebe Boswell, which fluently combines pencil drawing on paper, charcoal drawing on the walls, installation, sound works, and moving image. Floor-mounted video works of the artist ‘submerged in the contested space between land and sea’ are particularly effective, allowing the audience an overhead drone’s-eye-view: a ‘watching over’ perspective which could be one of divine/parental protection, or of unconsented technical surveillance.

A trip to Tonight the World by Daria Martin at the Barbican also reminded us of the unanticipated audience and artwork interaction. A (non-interactive) video-game based projection was playfully intervened by a bored kid in attendance: equally frustrated, bewildered and entertained by seeing a video game he was unable to play, instead performing his own manoeuvres in reaction to the presented digital landscape.

Technology & the near future – What does the near and distant future of technology hold for the way we will experience art and everyday life?

At Machine Rooms we discussed the possibilities of digital distribution of art works and design products – where instructions, codes or patterns can be shipped rather than physical items. Construction can then happen sustainably on location, ideally using locally-sourced and recycled/recyclable materials, with local makers. In a way this does happen increasingly with digital/installation based artwork loans: entire exhibitions could be emailed as videos, documents, files and data to be pieced together in physical space. Even more exciting is to imaging this application more widely in everyday consumer culture: we are not far from a future with 3D printed custom shoes, clothing machine-knitted-while-you-wait, and furniture made only on demand and from local wood. New making has the potential to seriously change our relationship with objects around us, and to reconfigure the supply & demand chain.

Genetic Automata at Arts Catalyst, an engaging video installation by Larry Achiampong and David Blandy, effectively draws together video gaming, biology, technology and identity. As contemporary thinking often jumps excitedly to transhuman, cyborg and avatar futures, the artists take pause to consider the historical narratives of evolution, classification and segregation. From home DNA-ancestry kits to digitally manipulated computer avatars, the project ‘explores the legacy and language of concepts around eugenics and human agency’.

Is This Tomorrow? at Whitechapel Gallery also sets out to speculate on near futures: pairing 10 artists and architects together with a fairly free reign to imagine ‘tomorrow’ (inspired by their landmark exhibition This Is Tomorrow in 1956). Unfortunately, considering the scope, many of the works fell a little flat in terms of presence and ambition – but perhaps we are all increasingly fatigued by visions of globally-warmed and war-torn dystopian futures. A powerful sculptural & video installation by Andre Jaque / Office for Political Innovation / Jacoby Satterwhite unapologetically combined nature, technology, architecture, sex, life, death, queer culture and fracking for the most likely vision of the future yet: hybrid, messy, risky, exciting – and a little bit hopeful amid the chaos.

Further recommended exhibitions include: The Idle Institute at Xero Kline Coma, Snow Crash at IMT Gallery, and Anna Chrystal Stephens at Space Gallery. Thanks also to the following for further talks & visits: Somerset House studios, Living with Buildings at The Wellcome Collection, Mimesis at the Imperial War Museum and Tate Collectives.

Spare Parts at The Science Gallery