There’s a room with a view in the University of Salford. Well, to be more precise there’s a room with the views. The views of artist Albert Adams. All great artists give us something of themselves in their work. Whether it be the choice of composition in a landscape, the expression that captures the hint of the person in a portrait or the telling combination of shape and form in a still life. What Adams gives us is even more powerful. His work confronts the harshest of realities, hate, persecution, the terrible cruelties we inflict upon each other. He condenses all that to symbolic imagery that provides a means to awaken the conscience, to make you see. Albert Adams (1929-2006). His name has that ring of colloquial northerness to it. Yet he was an artist very much from the south. A south that didn’t want him. South Africa.

Albert Adams has subsequently been called South Africa’s greatest 20th Century expressionist artist and yet he was a second class citizen in his homeland under apartheid. Of mixed race (his father was Indian, his mother African) he showed considerable artistic promise from an early age, but was refused entry to the School of Fine Art in Cape Town, purely because of his skin colour. Talent will out though, and in 1953 he won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London and ultimately he made this country his home.

As you enter the Albert Adams room in the Old Fire Station on campus the incendiary power in the 11 images it contains is tangible. Dark etchings scratched with the urgency of the metaphorical message they carry, brooding self-portraits and strange animals provide an unsettling welcome. However, the works draw you in through the sheer sense of artistic grit and verve that has created them.

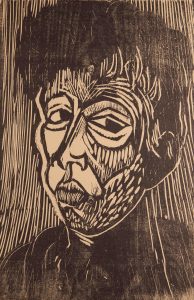

Adams himself is here, in two self-portraits from 1958. One in oils, one a woodblock print. Both are two thirds profiles and in both Adams warily meets your gaze. They are bold and youthful, but there is apprehension there too. Apprehension that perhaps stems from being disowned. Though by 1958 Adams was a student in the Expressionist artist Okcar Kokoschka’s School of Vision, and indeed a respected friend to the great man. These portraits, where Adams alone confronts himself, reveal an uncertainty of his own image, of his own place in the world. A year later in 1959 Adams had his first exhibition in Cape Town, but he was already a watched man liable to be arrested and thereafter never truly returned home again, though South Africa is ever part of his work. “I’m not South African. I never was South African. I was never allowed to be South African.” he said.1

Two etchings on display depict the conflict of apartheid. In Lamp, 2002, a paraffin lamp burns in a dark cell, its glow hardly reaching inches beyond its glass cover. This image is part of a series called Incarceration, works that were inspired by Adams visit to Robben Island where Nelson Mandela was held prisoner for 18 of his 27 years in jail. Mandela’s cell was very sparse, 8ft by 7ft with just a straw mat to sleep on. Is the lamp a physical representation of that hardship or a metaphorical representation of the imprisoned light of the father of modern South Africa? Albert Adams’ work makes you ask such questions, it makes you consider the plight of others, it reminds you to question the past and remember its relevance. The second image embodies the frustration of apartheid. A figure, whose head has been scribbled out, stands behind a power cable with plug hanging from above. The means for power is ever just out of reach for the faceless.

Albert Adams would often obliterate faces in his work, making figures anonymous, figures who like himself had been purposefully excluded in some way. In the large pencil figure drawing in the room the face of the man is hidden in dark shadow, only his ear is clearly visible. He can hear us though he is afraid to show his face. The dense blackness of the shadow has taken some considerable time to build up making this, I think, a more contemplative image than just a life drawing. Adams had more than one reason to hide his face. Even in his exiled home here in England, his race and sexuality forced him into the shadows. The result is a strong, edgy figure that disconcerted one visitor so much that they asked for it to be removed from the room. It is not a controversial image, what troubled that viewer was being confronted by raw emotion capable of rattling sensibilities.

Fear of discovery is present in the oil painting Wild Animal. A red dog shies away from our gaze; its head bowed, out of sight as it skulks toward a grey wall. That wariness gives Albert Adams a rare skill. He knew how to create visual metaphors. His work is filled with iconic symbols, elements that distil to an essence bold strong commentary. Adams knew the dark and dangerous line he trod in his work. His metaphor for that is the tightrope. In another etching, almost Chagall-like figures balance not just on the high wire, but on unicycles on the high wire. Edward Glennon, Albert’s partner contemplated these tightrope images when interviewed by Jeremy Kuper, for the African Mail and Guardian, “It’s how we all go through life” he said, “We’re balanced on a tight rope and we can go to disaster.”2

In his later etchings apes have a changing metaphorical role. There are two etchings with baboons riding skeletal creatures that are a stark depiction of the genocide in Darfur, Sudan from 2003. One ape has a dark cloak that flows, flame like up into the air. It carries a scythe in a most bestial representation of the grim reaper. The use of the ape here is a truly powerful metaphor. Adams is portraying genocide and it’s perpetrators as a reversal of evolution. They are the beast we evolved from, but are seemingly all to willing to return to. Yet Adams had a gentler relationship with baboons as well. He was born in Johannesburg and has told of how the family moved to Cape Town “at the age of four I travelled with my mother and sister, a baboon soft toy and my comfort blanket.”3 There is perhaps an echo of that toy in the etched portrait of a baboon that hangs in the corner of the room, its fur a multitude of dark lines, the long face with sad eyes and outstretched arm. He seems to be gazing out in sadness at the misery we human beings create in our world.

This piece entitled Seated Ape was completed in 2006, the year Adams died. Age though did not diminish his skill and could not diminish his perceptive eye.

The University was gifted a collection of Albert Adams work by his partner Edward Glennon through the Art Fund in 2012, this room gives home to a small number of images that encapsulate the work of a great artist. An artist whose ability to distil the evils of our world to expressionist symbols has a primal quality that forces us to recognise the wrongs we so often turn a blind eye to. Recognition of Albert Adams genius is still to come, at least outside of South Africa, but the power of the images in this room will remain with anyone who enters for a long time. His work will not easily be forgotten.

Danny Morrell, August 2017.

With thanks to Jennifer Iddon, University of Salford Art Collection, who arranged for me to visit the Albert Adams room and who provided documents that have informed this piece.

- Adam’s delicate balance, Jeremy Kuper, African Mail and Guardian 15th May 2009. https://mg.co.za/article/2009-05-16-adamss-delicate-balance

- Adam’s delicate balance, Jeremy Kuper, African Mail and Guardian 15th May 2009. https://mg.co.za/article/2009-05-16-adamss-delicate-balance

- Albert Adams obituary in the Independent by Tim Bruce-Dick