We’re pleased to be working with artist Jack Tan on one of six new artist commissions this Summer. His project Tale As Old As Time addresses important moments in Chinese civil rights history in the UK – read more about Jack’s project here.

Update: September 2021:

The artist is withdrawing from completing A Tale as Old as Time due to allegations of institutional racism at CFCCA. He is part of a group of artists calling for a defunding of the organisation.

Although his experience of working with the University of Salford Art Collection is positive, he feels the commission is currently untenable because the wider University is represented on the board of CFCCA.

In our Q&A, Jack talks more about the tradition of ‘disaster ceramics’, the history of Chinese disasters in the UK and the ‘civil rights moments’ he is highlighting, as well as his background and practice – in conversation with Stephanie Fletcher, Assistant Curator, University of Salford Art Collection.

Please note, this article includes references to racist language and incidents. If you are affected by these issues, please refer to the resources section at the end of the page; alongside petitions and campaigns that you can take part in.

Stephanie: Firstly, can you give us an introduction to your practice and artistic background? How does this work relates to your research interests and previous projects?

Jack: I discovered art quite late and only started training in my early 30s. Before that, like any good Asian kid, I was supposed to be a lawyer. I went to Law School in Hull, then worked in various paralegal and legal secretarial jobs before training at a commercial law firm, as well as doing civil rights campaigning and pro bono case work alongside. I started doing pottery at a local arts centre and one thing led to another, and I ended up leaving the law to go to art school to study ceramics at Harrow/University of Westminster.

Since then I have mainly been creating art installations and performances that explore aspects of the law or social justice. For instance, I created a work called Karaoke Court in 2014 that adapted arbitration law in a way that allowed people to resolve real disputes under binding arbitration contracts by singing karaoke before a jury-audience who would decide the verdict. This reforms litigation as a hostile activity into a fun and conciliatory one. In another work called Four Legs Good, I took over the bottom floor of Leeds Town Hall for Compass Festival 2018 converting it, signage and all, into a working Animal Justice Court where we revived the medieval animal trials for a day with modern cases argued by real advocates on behalf of live animal litigants.

Right now, I am working on an intergenerational education project where we are creating a new game app together that allows the player to roleplay a non-human and to lobby local councils to change planning and environmental policies from the non-human person’s viewpoint. This commission, Tale As Old As Time, however takes me back to my first love which is pottery, but allows me to combine it with social justice concerns and my interest in critically examining the effects of law and government policy on the Chinese community in the UK.

Stephanie: Can you tell us a little more about the tradition of ‘disaster ceramics’ that this work continues?

Jack: Disasters have been depicted on ceramics for a long time but often from the perpetrator’s or conqueror’s point of view. You see this for example in ancient Greek or Roman vessels or murals of war or invasion. But I am interested in a 19th century British tradition and the visual impulse to commemorate major public disasters on everyday pottery. Teapots, mugs, plates and other vessels were illustrated with disaster events to raise money for victims, to campaign for political awareness or simply to commemorate and commit these events into a material that is as long-lasting as bronze or stone, but much cheaper.

Events such as the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, where cavalry troops charged into a large crowd protesting the Corn Laws and killed 18 people and injured 650, was remembered quite viscerally on ceramics. Major industrial disasters were also commemorated in pottery such as the Oaks Colliery Disaster of 1866 in Barnsley where 361 miners died in two massive methane explosions. Tableware and figurative pottery was also used as awareness raising tools in political campaigns, notably the abolition of slavery movement in the early 19th century. This pottery, depicting slavery scenes of abuse and political slogans, circulated within domestic settings alongside pamphlets arguing for the abolition of slavery. The famous potter Josiah Wedgewood himself commissioned an anti-slavery medallion which he distributed freely in support of the anti-slavery movement. While it might seem like ‘bad taste’ now, at the time it was an important way to make sure that these stories were not forgotten, and remained a part of everyday life and history. The tea sets in this commission will depict disasters in a similar way, except they will use a more contemporary design language and commemorate my view of major events experienced by Chinese people in the UK.

Image : A historic example of ‘disaster pottery’.

Commemorative pot from the Oaks Colliery Disaster, Barnsley (1866). Over 360 men and boys were killed by an explosion – England’s worst ever mining disaster.

Source & copyright: National Coal Mining Museum for England / NCM.org.uk)

Stephanie: What are the other key moments in history that the works will discuss – and how has Covid 19 continued these narratives?

Jack: I am making five tea sets which are inspired by significant events in British Chinese civil rights history. But I make three caveats here. First, I am not a keeper of British Chinese history and consider that there are many histories of the Chinese in the UK. Secondly, what is significant to history is for the community to decide. However, events that appear in the tradition of commemorative disaster ceramics tend to be those that have gained visibility in the public consciousness through newspaper reporting. As such, I chose events that have been reported in the recent news. Finally there are of course more than five significant moments. But time and budget constraints meant that I had to choose only five. So this is really a snapshot of a political history of the Chinese in the UK from the viewpoint of an artist:

- the deportation of Chinese seamen from Liverpool (late 1940s) and their surviving children’s ongoing search to find their disappeared fathers;

- the violent murders of takeaway workers like Simon Tang (2013) and Migao Chen (2005);

- the mass drownings of Chinese cockle-pickers at Morecambe Bay (2004), which relate to other mass deaths at or around the sea in Dover (2000) and Essex (2019);

- the official blaming of Foot & Mouth disease (2001) on the Chinese; and

- racist attacks against Chinese people or anyone who looks Chinese during the Covid 19 pandemic (2020) .

I see the way that Covid 19 has emboldened casual racism and violent racist attacks against Chinese, East and Southeast Asian people as a direct result of a history of anti-Chinese racism in the UK. Starting from the Opium Wars (1839-42), when the victorious British forced China to buy opioids in exchange for tea, porcelain and silk leading to mass drug addiction in the population, to the Ministry of Agriculture blaming Chinese restaurants for the national outbreak of Foot and Mouth disease in 2001, the Chinese, Chinatowns and Chinese bodies have been framed in the UK as containers of disease, crime, seediness, forgery/deception and clandestine or covert invasion. In an increasingly hostile environment against non-Whites and migrants following the Brexit vote and the election of an openly racist and homophobic Prime Minister, the racialisation of the coronavirus pandemic has given license for the latent racism in the general population to erupt into attacks against any person or business perceived to be Chinese.

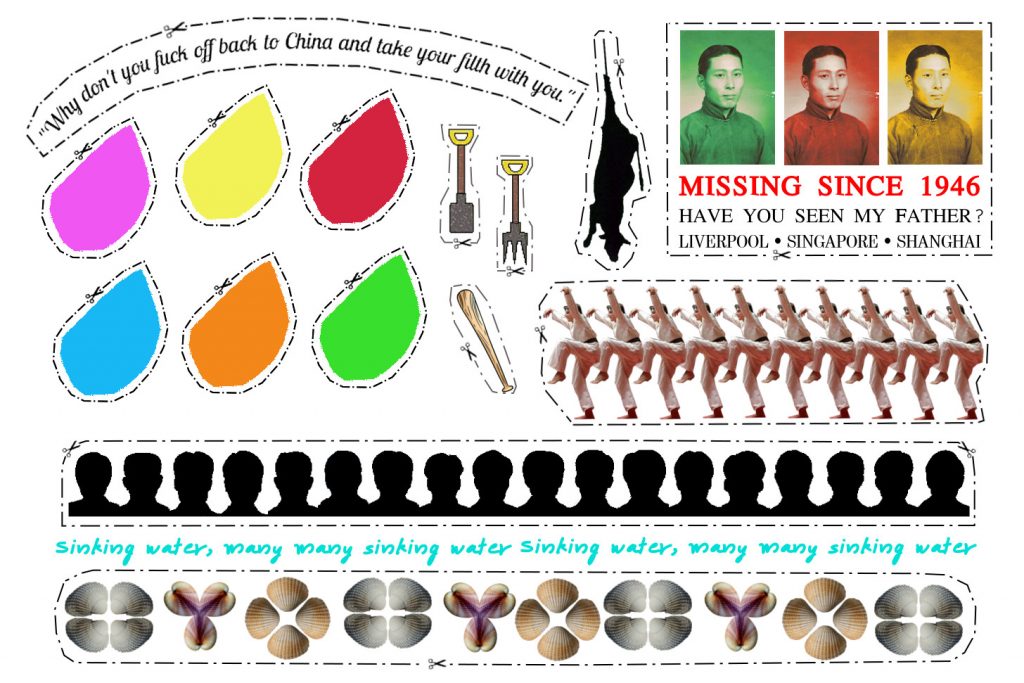

Stephanie: can you tell me more about the images you have used?

Jack: This image is a work-in-progress sample of a typical digital file that would be converted into ceramic waterslide decals. This is a process where artwork images are printed onto decal paper, a kind of transparent acetate-like film, using ink made from raw ceramic glazes. The individual images would then be cut out, immersed in water, and then slid onto pottery before being fired in the kiln. This digital sheet contains sample patterns and images that will be applied onto 5 bone china afternoon tea sets that will comprise the artwork Tale As Old As Time.

Starting at the top left corner:

- For a tea set highlighting Covid 19 racism, “Why don’t you fuck off back to China and take your filth with you” was a phrase whispered to British Chinese film-maker Lucy Sheen by a White man on a London bus during the Covid 19 pandemic in February 2020. Below, the multicoloured teardrops are derived from the shape of bruise marks on the face of Singaporean student following a violent racist attack on him in February 2020 by two teenagers who shouted ” I don’t want your coronavirus in my country” as they kicked and punched him.

- The garden spade, garden fork, baseball bat and repeated kung fu figures comprise decorative elements of a tea set that will draw attention to the vulnerability of Chinese takeaways who experience racist violence. In particular, CCTV footage of a fatal and ‘frenzied attack’ in 2005 showed youths adopt a ‘karate kid’ stance to mock Mr Chen, a takeaway owner, before the gang of 20 children and youths beat him to death with bats, poles, spades and heavy tree branches.

- The silhouette of a hanging cow represents the 2001 foot and mouth epidemic. The Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food briefed journalists that the Chinese community had introduced the disease into the country through smuggling contaminated meat for restaurant use. This saw an increase in racial attacks against the Chinese, East and Southeast Asian communities but it also led to the first mass Chinese political protest in British history. This tea set commemorates Chinese community grassroots activism and organising.

- The triptych of portraits at the top right shows a merchant seaman who had been separated from his British wife and children in the mid 1940s, and under deportation orders was expelled to China possibly via Singapore along with all other Chinese sailors living in Liverpool. The surviving children of these missing fathers are still looking for them and any information about them today: http://www.halfandhalf.org.uk/missing.htm. This tea set considers discriminatory laws and policy enacted in order to expel, penalise, obstruct or target the Chinese community, Chinese people, Chinese trade or culture in Britain.

- The silhouettes and shell patterns at the bottom of the decal sheet will decorate a tea set commemorating the Morecambe Bay disaster in 2004 where 23 unauthorised trafficked Chinese cockle-pickers got stuck in the sand and drowned as the tide came in. The words in blue “Sinking water, many many sinking water” were uttered in desperation by one of the cockle-pickers in a 999 call to the police before he drowned.

Very much like the tradition of 19th century disaster pottery, these contemporary tea sets will similarly depict political events using the decorative motifs typically seen in ceramic tableware, such as the use of polka dot design, stripes, edging patterns, or pastoral and action scenes. The Covid 19 tea set for example will create a cognitive dissonance between the whimsy of its multi-coloured teardrops and attractive cursive writing, reminiscent of Emma Bridgewater pottery, with the tea set’s traumatic subject matter. The potential activation of this artwork through the rituals of taking afternoon tea also opens up questions about how and what it means to embody or ingest a culture of colonialism or institutional racism today.

Share your thoughts:

Using the hashtag #PoliticalPottery

You can find us at:

twitter: @UoSArts / @jackkytan

Instagram: @uos_artcollection / @jackkytan

Resources:

CARG – Covid Anti Racism Group

The page includes news, blogs, petitions and resources, including information on reporting hate crime and where to find help.

Sign the Petition – Say No to Racism targeting British East Asian People

Sign the Petition – Stop depicting East & South East Asians in Coronavirus related media

Join the Crowdfunder – End the Virus of Racism

University of Salford Students can visit the Student Hub AskUs page for information on wellbeing, support, & reporting incidents.